This article was originally published in Off Chance Magazine

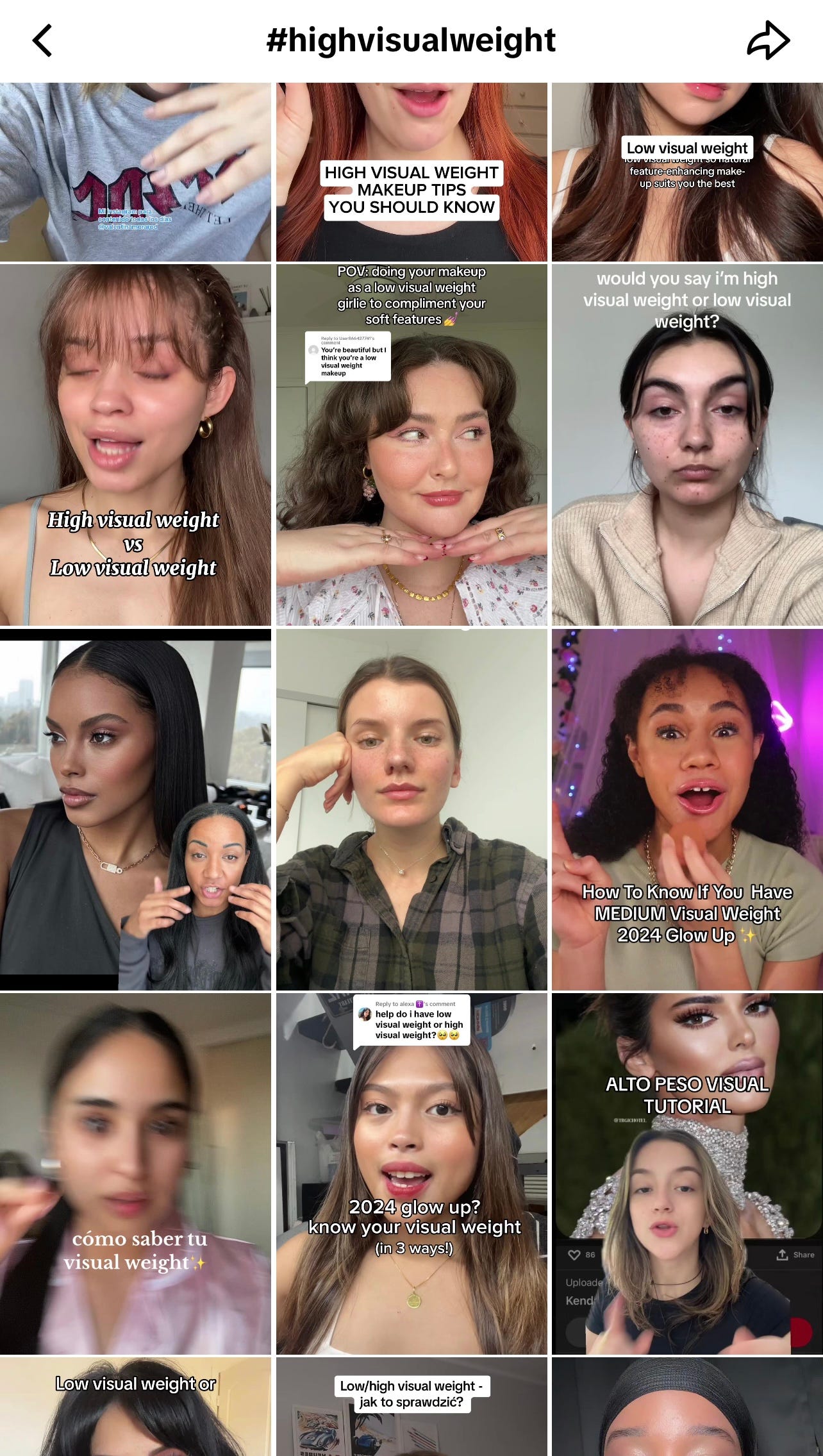

“The day you learn whether you have high or low visual weight is the day you instantly increase your pretty privilege,” @kandykapelle, TikTok creator, opens her video, with over 639.6K likes she promises that this is the key to being perceived as “10x more attractive”. High and low visual weight, the latest terminology cooked up by TikTok, is a cheat code to achieve instant prettiness, well according to the internet.

TikTok has a long and complicated relationship with the idea of 'pretty,' and high and low visual weight is just the latest iteration of a lineage that includes boy pretty, girl pretty, frog pretty, fox pretty, siren pretty - and that’s just to name a few. What do they all mean? Well, after hours of scrolling, I’m still not any closer to knowing. TikTok has made it an art to categorise pretty whilst pedalling it as a currency for success. Is this why this type of content does so well? We're taught from a young age, that success is the highest achievement. Success equals happiness, or so you might think, and all of this content provides the secrets to attain it. But does it make you happy? You can mould and shape, make smaller and bigger, but will it ever be enough? It’s a slippery slope, leading to intoxicating highs which we are left chasing.

“I can’t help but feel worried for the younger generation,” voices TikTok viewer Mary Baker. “I don’t absorb this type of content; you develop filters through experience and age. But the younger generation, who are subject to hours and hours of this content and who haven’t necessarily developed these filters, it’s scary to think what the unconscious intake is doing to them”. The pandemic invited a surge in screen time among young children, a recent study found that young children are spending up to 83 minutes more online a day. Facebook's internal research found that Instagram, makes eating disorders and thoughts of suicide worse in teenage girls, whistleblower Frances Haugen gathered internal documents from Facebook before submitting her resignation at Meta.

The research doesn’t paint a pretty picture. For some, the conversation around prettiness is frivolous but the disregard for the impact on mental health is enraging. According to The British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons, it saw a 102% increase in cosmetic surgery in 2022. In the U.K. an estimated 900,000 Botox injections are administered each year. Thanks to the accessibility and a wave of normalisation of tweakments, botox and fillers are not only reserved for a certain group of individuals, they’re for everyone. I remember growing up and thinking that Botox was only for people in their 60s but in my early thirties, I’m told it’s something I should consider. It’s in equal measures frightening and exhilarating. Cosmetic clinics offer a quick in-and-out option, with no down time, to help you look your best and thus live your best life - and you can literally do it in your lunch break.

We’re seeing more and more people yearn for this idealised pursuit. Girl pretty? A dewy glowing primer will help you achieve that. Deer pretty? Go ham with the blush. High visual weight? Try bolder makeup. Frog pretty? Book an appointment with a plastic surgeon. Siren Pretty? Consider a temple lift. And because beauty has been positioned as “good” and everything that is not beautiful, is considered as “bad”, painful and often dangerous procedures are viewed positively. Take for example the celebrity cheek surgery, also known as Buccal Fat Removal, which is one of the most sought-after surgeries of the last year and the hashtag has been viewed over 215.4 million times and that’s just TikTok only. It’s an endless cycle, we continue to get drunk on this idea that we must squeeze ourselves into these rigid categorisations of pretty, fueled by our insecurities.

As an idea that’s nothing new; it’s a play straight out of the beauty industry marketing book. For centuries, it’s sold us the idea of prettiness on the back of our insecurities. In many ways, it acts as a tool of oppression, metastasizing ideas of sexism, racism, ageism, and ableism to all parts of society, generating more insecurities. And so we continue to be stuck on this hamster wheel. It’s as futile as TikTok’s quest to contain and standardise what it means to be pretty; it remains perpetually out of reach.

You could perceive this content as quirky, fun, and even as women’s empowerment in a society that has dictated what is and what isn’t pretty for far too long, but underneath the surface, it’s doing more harm than good. “It doesn’t sit right with me; the fact that this content is always showcased as the answer to success, it’s the key to change your trajectory, the solution to all your problems,” Mary tells me. Masquerading as beneficial and valuable, only to act as fuel to feed this desire to be something else. In an ugly turn of events, we become the force feeders of this message.

“I don’t think prettiness means anything anymore” content creator Selena Yusef argues. “Beauty in its processes is commodified. They can be learned, applied, and worn like battle armour by anyone at any time,” Selena explains. “I think there is a sense of freedom that comes with disconnecting from these standardised ideas.” Beauty PR Consultant, Farrah Gray echoes this, “I think the issue is the lack of critical analysis of the messages we are exposed to about beauty.” This reminded me of Jia Tolentino's New Yorker feature, The Age of Instagram Face, where she discusses the rise of a new uniformed face, birthed by social media. She says “Technology is rewriting our bodies to correspond to its own interests—rearranging our faces according to whatever increases engagement and likes.” For the first time, she was able to articulate this bond of social media and our view of prettiness. While it seems obvious its impact, it’s striking to see it laid on paper, well screen. The Instagram face was just the beginning, today with TikTok we’re experiencing a global pandemic, and we’re none the wiser.

As a beauty editor, it’s my job to stay on top of beauty trends and standards, and as a consumer, it’s my role to give life to them. But I feel as though I’m living in a relentless make-believe universe, where everything is beyond our grasp. It’s hard to distinguish where being ‘pretty’ starts and where it ends. I question whether I really understand what it means to be pretty, and if it’s not just something I’m told, which inevitably changes with the times.

In Greco-Roman and Ancient Egyptian cultures, beauty was related to the divine, a tool for celebrating and communicating spirituality. In today’s world, pretty means something completely different; for some, the idea is entrenched in sexism— all of the 'isms’, while others wholeheartedly embrace the concept. Whatever interpretation of prettiness we're living through, maybe it’s time we break the chokehold it has over us.

What do you think?

everytime I hear about a new dating or beauty theory that originated on tiktok, I am grateful I deleted the app a year ago. its goal is to make you hate yourself.

This is a really great read, thank you! I think about it all the time