TikTok Translator: TikTok Makeup Contrast Theory Explained

Well sort of, I'm still trying to get my head around it

Welcome to my new series TikTok Translator. TikTok is awash with beauty trends, but what do they all mean and should we be taking any notice? As a self assigned TikTok Translator, I’ll be doing the hard work to let you know which ones are worth the hype and which ones you can skip.

I like to think that when I apply my makeup, it’s purely for myself - an expression, not an effort to make myself “prettier.” But recently, I’ve started second-guessing this. How much of my makeup routine is actually for me, and how much is influenced by society’s beauty standards?

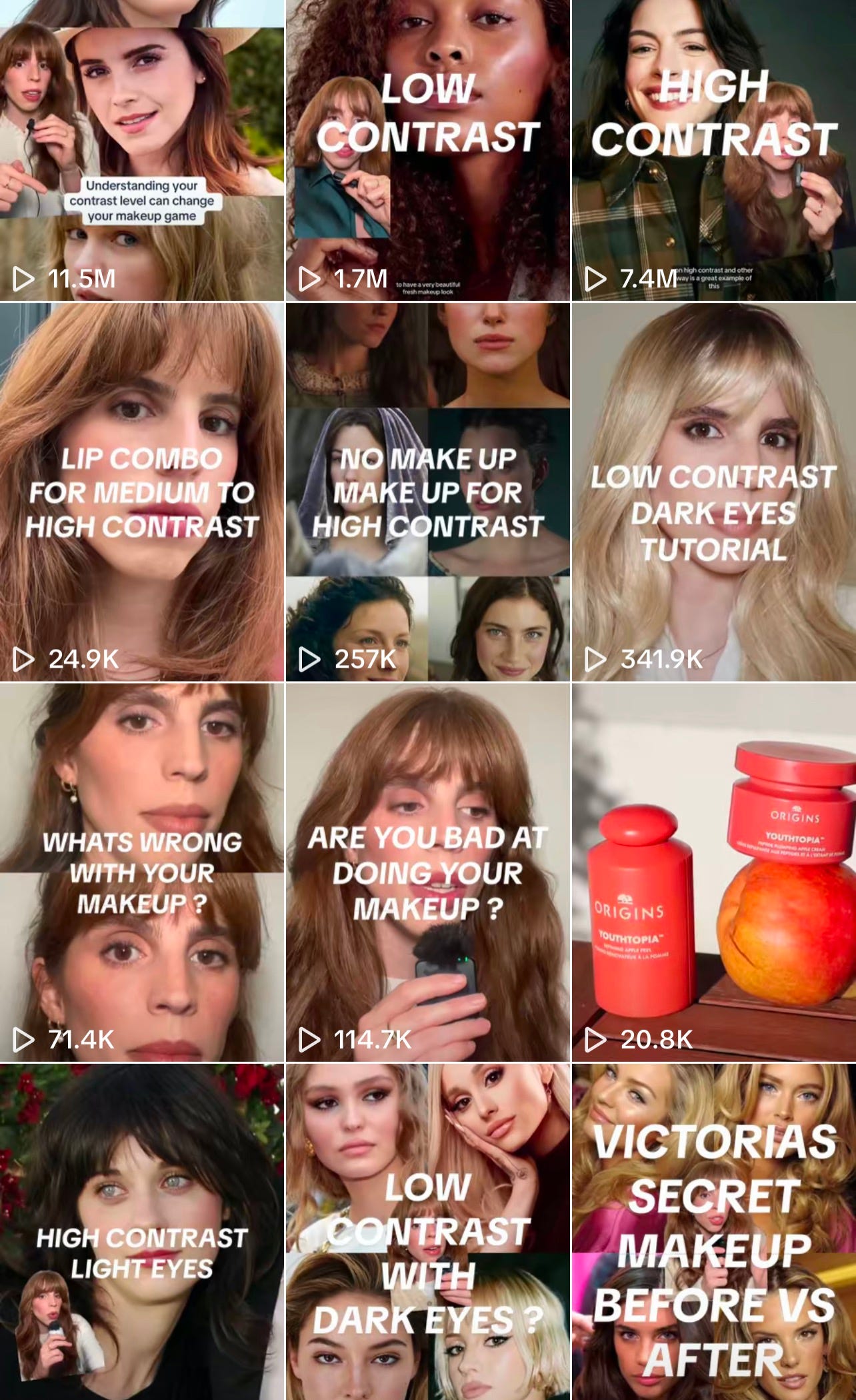

I’ve scrolled enough TikTok to become well acquainted with the latest beauty trend, “face contrast makeup.” I’m sure you haven’t missed it either. It’s everywhere, and the videos always start in a similar way, as though the creators are members of some secret cult: “You’re not ugly, you’re just doing your makeup wrong.” Say what you will about the opening line - it’s striking, and it definitely stopped me in my scrolling tracks. It’s a subtle (yet nasty) play on our desire to be considered beautiful, offering a “solution” for self-doubt.

With over 11.5 million likes on the original contrast video, the trend is gaining huge traction. Popularised by French makeup artist Alienor, face contrast makeup is about analysing your natural facial contrast and applying makeup to enhance it, supposedly achieving optimal results. In the wildly popular video, Alienor explains, “contrast is everywhere” for her, it’s not a trend; it’s a “fact.” She’s on a mission to help you understand your face and how your makeup will look on it, aiming to make you feel more confident, and of course with better makeup application.

On the surface, it might seem well-meaning - even empowering, at a stretch. But how different is it, really, from every trend before it? At its core, the message remains: there’s a right and wrong way to do your makeup, and, ultimately, a right and wrong way to be beautiful.

The pressure to follow beauty trends means constantly looking outside ourselves - to influencers, apps, or the internet as a whole. There’s always an external source to dictate how we should look. Face contrast makeup isn’t a new idea, nor revolutionary; it borrows from older theories suggesting that higher facial contrast signals attractiveness. Edmund Burke explored this concept in his 1757 book, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, where he discussed how contrasts, like light and shadow, create allure. Today’s iteration tells us that we too can achieve this allure and “balance” by identifying our natural facial contrast level and applying makeup accordingly. Conveniently, Alienor has even created a filter, so you too can figure out your contrast level without even leaving the app.

I gave the filter a go myself, yet I’m still unclear about my “contrast level.” The filter’s design is quite simple, feels limited, and struggles to identify contrast on darker skin tones. For Black and Brown women, this is nothing new. It speaks volumes about how the beauty industry regards women of colour.

Filters and trends like face contrast makeup rarely account for the full spectrum of skin tones and features, reinforcing the message that beauty aligns with whiteness. When creators like Gloria speak out about this, they’re often met with backlash or even racist abuse, highlighting how far the industry has yet to go. The result is a frustrating cycle: while brands promote inclusivity, their actions often feel tokenistic, leaving women of colour feeling both visible and marginalised. It’s a reminder that inclusivity in beauty must go beyond words and extend to products and standards that truly reflect all faces.

For a younger generation, these standards are particularly tough. I spoke with Maya, a 16-year-old who shared, “It’s exhausting, to be honest. Trends like face contrast make it feel like you’re always not good enough and I feel ugly. My friends and I try these things, but we can’t keep up. Even if it’s ‘just for fun,’ we all know there’s pressure to look good.”

Research has consistently shown that social media can have a significant impact on young people's confidence and self-esteem. A 2019 study by the Royal Society for Public Health found that Instagram, in particular, contributes to feelings of inadequacy and anxiety among young users, primarily due to the constant comparison to idealised images. Social media often portrays unrealistic beauty standards through filters and edited content, leaving many teens feeling that they fall short of these ideals. I don’t know who can keep up with the trends and remain unaffected by them, let alone young teens who are going through so much as it is.

Considering how fleeting these trends are, the pressure to conform remains firm. Whether it’s contouring, “no-makeup” makeup, or face contrast, the message is always the same: there’s a right way to look, and that way can always be “improved.” Beauty standards may shift, but the cycle of adapting, reshaping, and “correcting” ourselves never ends.

TikTok influencers are translating this idea into a formula for “fixing” your face to fit an “ideal,” using makeup techniques that heighten contrast. Philology reminds us that how we discuss beauty - and, by extension, how we define it - reflects cultural values and power dynamics. Face contrast makeup is less about empowering women to celebrate their natural beauty and more about imposing yet another rule on how we “should” look to be socially accepted.

Historically, women’s appearances have been sites of control, with makeup often used to signify conformity or desirability. In Victorian England, bold makeup was a sign of rebellion or looseness, while in 1950s America, a polished face marked femininity and respectability. Today’s trends stem from the same roots, reinforcing that looking a certain way is still essential for approval, even if it’s presented as “choice.”

In an era where women’s empowerment and choice are emphasised, it’s jarring that we are still so often reduced to how we look. It’s not that we don’t know how to apply makeup; it’s that society has prescribed a single, “correct” way to look, persistently pushing us to conform to it.

So, the next time we see a trend telling us to “fix” ourselves, maybe we ask: what if we didn’t need fixing? What if beauty wasn’t the ultimate goal? What if feeling good wasn't dependent on understanding our facial contrast and working to conform to rigid ideals? Because there will always be a new measure, maybe we just take ourselves outside of the running?

Face Value is a “weekly” newsletter about beauty, culture, and the way we perceive beauty. If this is something you’re interested in, consider subscribing and sharing.